Bourbon

by

Terry Sullivan

During the 1700’s in Bourbon County, Kentucky the whisky business was booming. It was sent down the Ohio River where it could be transported out west or onward to New Orleans. At first it was known as Whisky from Bourbon County and later shortened to Bourbon Whisky. It wasn’t until two centuries later that Congress passed a resolution declaring that bourbon was a distinct product of the United States.

In order to be called bourbon, the whisky must:

• Be made in the United States (not necessarily in Kentucky)

• The grain recipe must contain at least 51% corn.

• Be distilled to less than 160 proof (80% alcohol) from fermented grain mash

• Be matured in new charred white oak barrels at no more than 120 proof

• Have nothing added to the final product except water

• Be bottled at 80 proof or higher

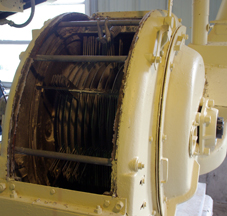

Bourbon begins with a recipe including at least 51% corn, rye and barley malt. Trucks deliver the grain to the distillery where it is tested. If the grain passes the test, it is dumped onto an area such as that in the first photo. If the grain is not accepted, it is returned. This is rare, but it does happen. The next step is to mill the grain. The inside of a corn mill is shown in the second photo.

Water is heated to the boiling point in a mash cooker (third photo). The milled corn is added. As the corn cooks in the water, rye is added. After the mixture cools a bit, barley malt is added. The mixture is then sent to a fermenter (fourth photo). Yeast is added to the mixture after the temperature cools to 64º F. The sugar in the mixture is converted to alcohol. This fermentation can last three to five days. While touring distilleries, look inside fermenters. When first added to the fermenter the mash has a slightly sweet taste. By the third day the mash has a sour taste as the sugar was converted to alcohol. While observing the mash, look for bubbles (fifth photo). Fermentation may be so active that the mixture is swirling.

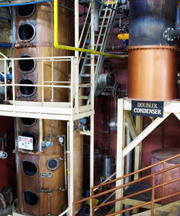

The fermented mixture goes into a still that creates an alcohol vapor. There are a variety of still designs used (photos six through eight). Many of the stills are made of copper. The vapor is re-condensed and then passes through a doubler to create a clear distillate. This liquid can have a high proof often over 120.

After the desired proof is reached, the distillate is placed in charred oak barrels. Winemakers use barrels that have been toasted. Think of making toast in a toaster. Bread toasted to a light tan to a brown is similiar to an oak barrel toasted light to medium plus. Now think of burnt toast. It is a black color. The distiller uses charred barrels that are black inside. The photo on the right shows two toasted oak barrels and two charred barrels. The majority of barrels built in the United States are manufactured at cooperages in Kentucky for the bourbon industry.

After the desired proof is reached, the distillate is placed in charred oak barrels. Winemakers use barrels that have been toasted. Think of making toast in a toaster. Bread toasted to a light tan to a brown is similiar to an oak barrel toasted light to medium plus. Now think of burnt toast. It is a black color. The distiller uses charred barrels that are black inside. The photo on the right shows two toasted oak barrels and two charred barrels. The majority of barrels built in the United States are manufactured at cooperages in Kentucky for the bourbon industry.

The barrel aging is perhaps the most important step in the process of making bourbon. Often these barrels are aged in century old buildings. Although bourbon can be made in any of the states, Kentucky's terroir is perfect for making bourbon. During hot temperatures, the wood of the barrel absorbs the distillate. The opposite occurs during cooler temperatures. It is the absorbtion and release by the wood that gives the clear distillate the dark gold or amber color of bourbons. In order to be called bourbon, the liquid must spend two years in the oak barrels. Bourbon that has been in the oak barrel for less than four years must have the number of years written on the bottle. The photos show a warehouse and barrels aging.

Like wine, some of the bourbon in the barrels will evaporate. Unlike wine, though, the distiller cannot top it off. Once placed in the barrel, bourbon cannot leave the barrel until it is bottled. It is not unheard of to open a barrel that is twenty-three years old to find all the bourbon had evaporated. About 1/3 to 2/3 of the volume of a barrel will evaporate over the eight to ten years that many bourbons are aged. Water is the main ingredient to evaporate thus increasing the alcohol level of the remaining liquid.

Use the same structured tasting for wine when you taste bourbon. Note the color, aroma, taste and finish. The Kentucky Bourbon Trail has eight distilleries as members. Take a tour and discover the history and process of making bourbon.